Okay, let's talk about jellyfish. You see them pulsing gracefully in aquariums, or maybe you've had a less graceful encounter with one at the beach. They look so simple, right? Just a blob of jelly. But then you start to wonder about the basics of life. How do these things, without a brain or a heart, make more of themselves? Specifically, how do jellyfish lay eggs? It's one of those questions that seems simple but opens a door to a world that's honestly pretty wild. I remember the first time I saw a cluster of jellyfish eggs under a microscope – it didn't look like anything I expected. It was messy, intricate, and completely fascinating.

The short answer isn't so short. It depends entirely on the type of jellyfish. For some, the classic idea of "laying eggs" is sort of correct. For many others, the process is part of a bizarre, two-stage life cycle that would put most sci-fi to shame. To really understand how do jellyfish lay eggs, we have to ditch our land-based, mammal-centric thinking. We're entering the realm of broadcast spawning, microscopic larvae, and creatures that can essentially age in reverse.

Core Concept: Most jellyfish don't "lay eggs" in the way a bird does. Instead, many release eggs and sperm directly into the water column in a process called spawning. The real magic (and complexity) often happens after that, involving a completely different life stage called a polyp.

The Two Faces of a Jellyfish Life

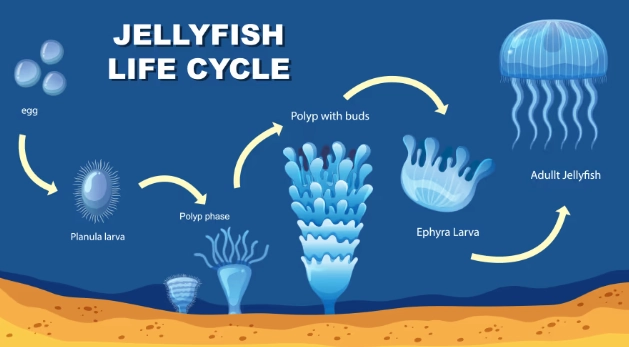

You can't really grasp how do jellyfish reproduce without understanding their two-form life cycle. It's like if a butterfly's caterpillar stage was a completely separate, sedentary animal that could also clone itself. This cycle is the key to everything.

First, you have the medusa. This is the form we all picture – the bell-shaped, free-swimming jellyfish. It's the adult, sexual phase. This is the stage that handles the "how do jellyfish lay eggs" part of the equation, at least initially.

Then, you have the polyp. This is the juvenile stage. It looks nothing like a jellyfish. Imagine a tiny, stalked sea anemone stuck to a rock, shell, or dock. It's sessile (doesn't move). Its job is to eat, grow, and eventually transform—through a crazy process called strobilation—into multiple baby medusae. The polyp is the asexual, cloning factory of the operation.

I think the polyp stage is the most underrated part of this story. Everyone focuses on the floating jelly, but the real reproductive workhorse is this tiny, stuck-on-the-bottom creature. It's the secret to their success, and honestly, it's a bit creepy in a brilliant way.

The Medusa's Role: Spawning and Fertilization

So, the adult jellyfish (medusa) is where the sexual reproduction happens. Most jellyfish are either male or female, though some species are hermaphrodites. They have gonads – reproductive organs – usually visible as colored, frilly-looking structures near the base of the bell or along the radial canals.

When it's time, males release sperm from their mouths or special pores. Females release eggs. This is typically a synchronized event, often triggered by water temperature, daylight length, or lunar cycles. They just broadcast their genetic material into the sea. No pairing up, no nesting, just a massive, watery genetic mixer. This is the most direct answer to "how do jellyfish lay eggs" for many species: they don't lay them in a nest; they simply let them go.

Fertilization happens externally, in the open water. Sperm swims to eggs, and if they meet, a zygote forms. This method seems haphazard, but when millions of gametes are released in a small area, the odds work out. The fertilized egg then develops into a tiny, free-swimming larva called a planula.

The planula looks like a microscopic hairy sausage. It swims with tiny hair-like cilia for a few hours to several days. Its mission? Find a suitable hard surface. This is a vulnerable time, and most don't make it. But the ones that do settle down, attach themselves head-first, and metamorphose into our next hero: the polyp.

From Polyp to Proliferation: The Asexual Powerhouse

This is where the story gets really interesting and moves beyond the simple "lay eggs" idea. The settled planula transforms into a single polyp. This little guy is a survival machine. It has a mouth and tentacles to catch food. And it can do some incredible things.

First, it can clone itself asexually. Through a process called budding, a polyp can grow tiny replicas of itself on its body. These buds can either detach to become new, independent polyps (forming a colony), or they can stay attached. This is how a single fertilized egg can give rise to hundreds of genetically identical polyps.

Second, and most crucially for creating new jellyfish, the polyp undergoes strobilation. When conditions are right (often in spring, as waters warm), the polyp begins to change. It elongates and develops a series of horizontal grooves, looking like a stack of tiny plates or saucers. These grooves deepen, and one by one, the top segments peel off and swim away. Each of these segments is a tiny juvenile jellyfish called an ephyra.

Think about that. One polyp can produce a stack of 10, 15, or more ephyrae. A colony of polyps can release thousands. The ephyra then grows and matures into the adult medusa, and the cycle is complete. So, when you ask "how do jellyfish lay eggs," you're often only seeing the first half of a loop that goes: medusa (sex) -> egg/sperm -> planula -> polyp (asexual) -> ephyra -> medusa.

Mind-Bending Fact: In some jellyfish species, like the common Moon Jelly (Aurelia aurita), the female medusa can actually hold eggs in special brood pouches on her oral arms. Fertilization happens internally (using sperm she captures from the water), and the planulae develop there for a while before being released. This gives them a slightly better start than total broadcast spawning. So even the "laying eggs" part has variations!

A Quick Guide to Jellyfish Reproductive Strategies

Not all jellyfish follow the classic medusa-polyp-medusa cycle perfectly. Here's a breakdown of the main ways they tackle the "how do jellyfish lay eggs" question:

| Reproductive Strategy | How It Works | Example Species | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Metagenesis (Classic Cycle) | Medusa spawns -> Planula -> Polyp -> Strobilation -> Ephyra -> Medusa. Both sexual (medusa) and asexual (polyp) phases. | Moon Jelly (Aurelia), Sea Nettle (Chrysaora) | Combines genetic mixing (sex) with massive population growth (asexual budding/strobilation). Highly resilient. |

| Direct Development | Medusa spawns -> Planula develops directly into a new, tiny medusa. No polyp stage exists. | Some Box Jellies (Class Cubozoa) | Simpler, faster life cycle. Good for species where the adult form is highly successful. |

| Brooding | Female medusa retains eggs on her body (in arms or pouches). Fertilization is internal or in pouches. She releases planulae, not eggs. | Some Moon Jellies, Upside-Down Jellyfish | Increased survival of early stages by providing protection. |

| Polyp Dominance | The polyp stage is long-lived and forms extensive colonies. Medusa stage may be brief, seasonal, or even absent in some related hydrozoans. | Freshwater Jelly (Craspedacusta), many hydroids | Colony provides stability and continuous asexual reproduction; medusae are for dispersal. |

Looking at that table, it's clear why a one-size-fits-all answer doesn't work. The box jelly strategy is shockingly direct compared to the moon jelly's convoluted path.

What Triggers Jellyfish to Reproduce?

They don't just do this randomly. Reproduction is an energy-intensive process, so it's timed to maximize survival. Key environmental cues include:

- Water Temperature: A primary trigger. Warming spring/summer waters often cue spawning in medusae and strobilation in polyps.

- Food Availability: Plentiful plankton means adults are well-fed and can produce gametes, and polyps have energy to strobilate.

- Photoperiod: The length of daylight. Longer days in spring and summer signal favorable conditions.

- Lunar Cycles: Some species, like the famous Palolo worms, have spawning synchronized with moon phases. Evidence suggests some jellyfish may also use subtle lunar or tidal cues for mass spawning events.

I've read about research stations that can induce jellyfish spawning in labs by carefully mimicking these natural cues – a slow temperature ramp-up combined with adjusted light cycles. It's not an on/off switch, but a careful orchestration by the environment.

Why Does This Weird Cycle Matter? (Beyond the Curiosity)

Understanding how do jellyfish lay eggs and their full life cycle isn't just trivia. It explains some major real-world phenomena.

Jellyfish Blooms: Those massive, sometimes nuisance, swarms of jellyfish? The polyp stage is the key. A seabed covered in polyps (on ship hulls, docks, aquaculture equipment, or seafloor structures) is a "seedbank." When conditions align – warm water, lots of food – all those polyps can strobilate in sync, releasing an army of ephyrae that grow into a bloom. It's like having thousands of time-release jellyfish capsules on the ocean floor. Control or understand blooms? You have to look at the polyps.

Resilience and Survival: This complex cycle is a survival masterpiece. The medusa disperses genes far and wide via its planktonic planula. The polyp is tough; it can withstand colder temperatures, lower food availability, and even some pollution that would kill the delicate medusa. If the medusa population crashes, the species can persist as polyps, waiting for better times to churn out new adults. It's a brilliant hedge against environmental uncertainty.

Aquarium Challenges: Ever wonder why it's hard to breed some jellyfish in captivity? You need to replicate the entire cycle. It's not just about getting adults to spawn; you need to catch the microscopic planulae, provide the perfect substrate for them to settle and become polyps, and then trigger strobilation with precise environmental shifts. It's a multi-stage headache, which is why many aquariums like the Monterey Bay Aquarium have dedicated, expert-run culture labs. Their public page on moon jellies gives a great, accessible overview of the life cycle visitors are seeing.

Common Questions About How Jellyfish Lay Eggs

Q: Do jellyfish have genders?

A: Most species have separate male and female individuals. You can't usually tell by looking, though sometimes the gonads are different colors. Some species are hermaphrodites, carrying both sets of reproductive organs.

Q: Where do baby jellyfish come from?

A: This is the crux of it! They come from one of two places: 1) From a fertilized egg that became a planula larva and then a polyp, which then released them as ephyrae (most common). Or 2) From a fertilized egg that developed directly into a tiny medusa (less common). The "polyp nursery" is the primary source.

Q: Can a jellyfish reproduce by itself?

A: The medusa (adult) usually cannot. It needs a partner's sperm/eggs for sexual reproduction. However, the polyp stage absolutely can reproduce by itself, through asexual budding. So the species can clone itself efficiently via the polyp.

Q: How many eggs does a jellyfish lay?

A: It varies wildly. A large female moon jelly might release tens of thousands of eggs at a time. A lion's mane jellyfish can release over 50,000 eggs daily during spawning season. They play a numbers game, as external fertilization is risky.

Q: Why are we seeing more jellyfish blooms worldwide?

A> This is a complex issue, but the life cycle is central. Human activities like overfishing (removing jellyfish competitors/predators), coastal construction (creating perfect polyp habitat on hard surfaces), and warmer waters due to climate change (extending the reproduction season) all favor the jellyfish's strategy. The resilient polyp bank exploits these changed conditions perfectly. Organizations like the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution have researchers dedicated to studying these blooms and their causes.

Wrapping Your Head Around It

So, how do jellyfish lay eggs? The initial act is often a simple release into the sea. But the journey of that egg is anything but simple. It's a gateway into a life cycle of astonishing complexity and flexibility, involving a shape-shifting, cloning, bottom-dwelling stage that is the true engine of jellyfish survival.

The next time you see a jellyfish, remember: you're only seeing half the story. The other half is likely stuck to a piling somewhere, quietly waiting to manufacture the next generation. It’s a system that feels both ancient and ingeniously efficient. It’s not the clean, familiar reproduction of animals we know, but in the vast, challenging ocean, it works. And honestly, it works a little too well sometimes, as those beach-closing blooms remind us.

If you want to dive even deeper into the biology of marine invertebrates, the peer-reviewed resources available through institutions like the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) are an invaluable, authoritative source for taxonomy and species-specific information. It's where the real nerds (I say that lovingly) go to get the details right.

Hopefully, that demystifies things a bit. The ocean is full of solutions to life's problems that are radically different from our own, and the jellyfish's approach to making more jellyfish is a prime, pulsating example.

Comment