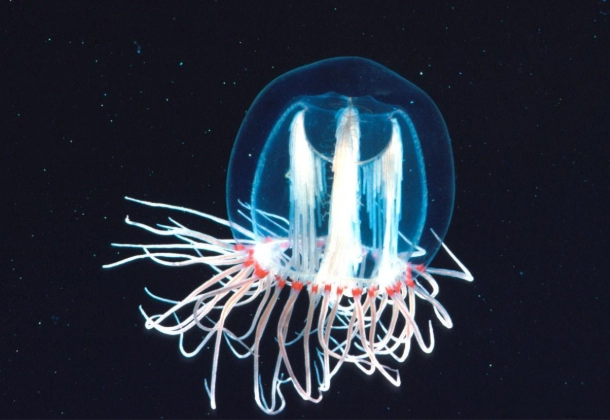

Let's be honest, when you think of jellyfish, you probably picture those ghostly, pulsating blobs drifting in the ocean. Reproduction might be the last thing on your mind. But let me tell you, asking "how do jellyfish reproduce sexually" opens a door to one of the most fascinating, head-scratching, and complex life cycles in the entire animal kingdom. It's not a simple boy-meets-girl story. Far from it.

I remember the first time I saw a jellyfish bloom, a massive swarm of them, at an aquarium. It was mesmerizing, but also sparked a ton of questions. Where did they all come from? How do they make more of themselves? The answer is a wild ride that involves sex, but also a complete transformation of body form, a sedentary stage that can clone itself, and environmental triggers that read like a sci-fi plot. If you've ever been curious about the nitty-gritty of jellyfish sex lives, you're in the right place. We're going to dive deep, and I promise it's weirder than you imagine.

The Core Concept: It's All About the Two Lives

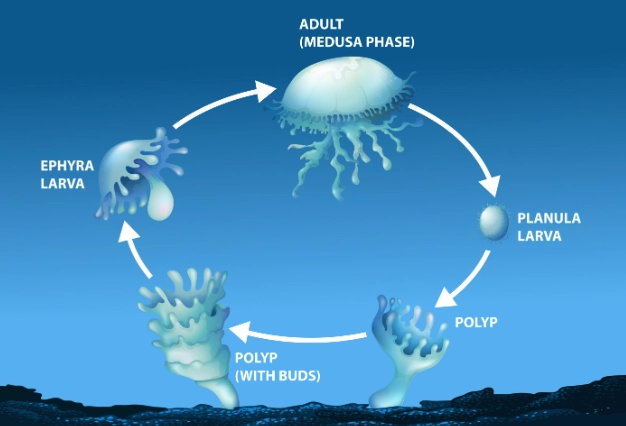

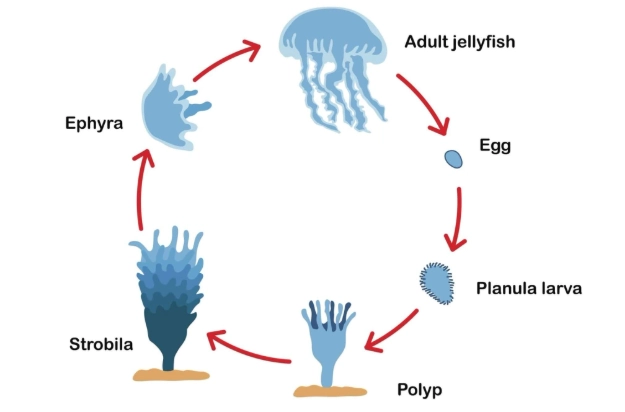

To truly grasp how do jellyfish reproduce sexually, you need to forget the idea of a single animal living one life. Most jellyfish (from the groups Scyphozoa and Cubozoa) have what's called a metagenetic life cycle. That's a fancy term for having two distinct body forms that take turns. Think of it as a biological relay race where one form handles sex, and the other handles making copies.

The two key players are:

- The Medusa: This is the form everyone recognizes—the free-swimming, bell-shaped, often tentacled "jellyfish." This is the sexual stage. Its sole reproductive purpose is to produce gametes (sperm or eggs).

- The Polyp: This is the hidden, often overlooked stage. It looks nothing like a jellyfish. Imagine a tiny, stalked anemone or a little tube stuck to a rock, seafloor, or even a boat hull. This is the asexual stage. It can clone itself and, crucially, it produces the next generation of medusae.

So, sexual reproduction in jellyfish doesn't directly create another jellyfish. It creates the founder of a colony that will then produce jellyfish. Wrapped your head around that? It's a bit of a mind-bender, but it's the key to everything.

The Sexual Phase: How the Medusae Do Their Thing

Alright, let's get to the act itself. The adult medusa is where sexual reproduction happens. But even here, there's variety.

Broadcast Spawning: The Oceanic Mixer

This is the most common method and answers the classic "how do jellyfish reproduce sexually" query. Jellyfish are mostly dioecious, meaning individuals are either male or female. When conditions are right (often linked to water temperature, daylight, or lunar cycles), males release clouds of sperm from their mouth or gonads into the surrounding water. Females do the same with eggs.

Fertilization is external and left entirely to chance in the vastness of the ocean. It seems inefficient, right? I used to think it was a terribly wasteful system. But when you consider the sheer numbers involved—millions of gametes released by thousands of individuals in a bloom—the odds improve. It's a numbers game on a colossal scale.

Brooding: A Bit More Parental Care

Some jellyfish species, like many in the order Stauromedusae (the stalked jellyfish), are brooders. Here, the female captures sperm from the water, but fertilization happens internally. The eggs are then held on the mother's body—often in special pouches on her arms or around her mouth—where they develop into larvae. This offers the embryos some protection, a rare bit of parental investment in the jellyfish world.

So, whether by broadcast spawning or brooding, the result of sexual reproduction is the same: a fertilized egg.

From Sex to Sessile: The Larval Journey

This is where the plot thickens. That fertilized egg develops into a free-swimming, microscopic larva called a planula. The planula looks like a tiny, hairy oval, and it uses those hairs (cilia) to swim. But it's not swimming aimlessly; it's on a mission to find a suitable spot to settle down.

This phase can last from hours to days. The planula is exploring the seabed, looking for the perfect patch of real estate—a rock, a shell, a piece of mangrove root, even the underside of a dock. Once it finds its spot, it attaches head-first and undergoes a radical transformation. It metamorphoses into our second key player: the polyp (also called a scyphistoma).

The Polyp Stage: The Unsung Factory

Now settled, the polyp enters a phase of growth and potential immortality. It feeds on tiny plankton, and here's where things get interesting asexually.

- Strobilation: This is the main event. When environmental cues signal it's time (often a seasonal temperature change or food abundance), the polyp begins to transform. It starts to segment, looking like a stack of tiny saucers. Each segment is a miniature, developing jellyfish called an ephyra. The polyp is essentially a factory assembly line. Eventually, these ephyrae detach one by one and swim away, starting their lives as young medusae. A single polyp can produce dozens of ephyrae.

- Budding: Polyps can also reproduce asexually by budding. They create genetically identical copies of themselves, forming small colonies. This is how a single successful planula can give rise to an entire polyp garden, all primed to release a small army of jellyfish later.

Some polyps can also enter a dormant state called a podocyst if conditions turn bad, waiting months or even years for better times. This resilience is a huge part of why jellyfish populations can explode seemingly out of nowhere.

A Detailed Look at Different Jellyfish Groups

Not all jellyfish follow the script exactly. Here’s a breakdown of how sexual reproduction varies across major groups. This table should help clarify things.

| Jellyfish Group (Class) | Common Examples | Key Features of Sexual Reproduction & Life Cycle |

|---|---|---|

| Scyphozoa (True Jellyfish) | Moon Jellyfish (*Aurelia*), Lion's Mane (*Cyanea*) | The classic model. Medusae are the dominant, conspicuous stage. They broadcast spawn. The polyp (scyphistoma) stage is small and often solitary. Strobilation is the primary method for producing ephyrae. |

| Cubozoa (Box Jellyfish) | Sea Wasp (*Chironex fleckeri*), Irukandji | Similar cycle but often more direct. The polyp stage is singular and can transform entirely into a single medusa (not always by strobilation). Some species have complex mating behaviors, with males transferring sperm packets to females. |

| Hydrozoa (Not "True" Jellyfish) | Portuguese Man O' War (*Physalia*), By-the-wind Sailor (*Velella*) | This is where it gets really complex. Many are colonial organisms. The familiar float is a colony of polyps. Specialized reproductive polyps (gonozooids) within the colony bud off tiny, often short-lived medusae that produce gametes. The life cycle emphasis is heavily on the polyp. |

| Staurozoa (Stalked Jellyfish) | Various stalked species | They live attached as adults (the medusa is stalked). They often brood their larvae. The planula develops directly into a new, tiny stalked adult, often skipping a distinct polyp stage entirely. This is a big exception to the rule. |

Looking at that table, you can see the Staurozoa really break the mold. It goes to show that in biology, there's always an exception.

Environmental Triggers: The Conductors of the Cycle

Understanding how do jellyfish reproduce sexually isn't just about anatomy; it's about timing. The entire cycle is orchestrated by environmental factors. The polyp stage is like a biological computer waiting for the right passcode.

- Temperature: This is the big one. A steady rise or fall in water temperature is a primary trigger for strobilation in polyps. Spring warming often signals the start of jellyfish season in temperate waters.

- Photoperiod: Changes in day length act as a reliable calendar for polyps, letting them know the season is changing.

- Food Availability: Polyps need to be well-fed to have the energy to produce ephyrae. A plankton bloom can kickstart the process.

- Lunar Cycles: Some species, like the famous Palauan *Mastigias* jellyfish, have spawning events tightly synchronized with the moon.

When these factors align, the polyp gets the green light. It's a finely tuned system that has allowed jellyfish to thrive for over 500 million years.

Why This Weird Cycle? The Evolutionary Advantages

You might wonder why such a convoluted system evolved. It seems overly complicated. But from an evolutionary standpoint, it's a masterstroke of adaptation.

- Genetic Mixing & Dispersal (Sexual Phase): Broadcast spawning mixes genes from different individuals, creating genetic diversity in the planulae. This diversity is crucial for adapting to changing environments and resisting disease. The planula stage also allows for dispersal to new habitats by ocean currents.

- Population Explosion & Persistence (Asexual Phase): Once a genetically diverse planula settles, the polyp can create hundredsof genetically identical offspring (ephyrae) with minimal energy. This allows jellyfish populations to explode rapidly when conditions are perfect (leading to blooms). The polyp's ability to bud, form dormant pods, and withstand harsh conditions acts as a "seed bank," ensuring the species survives even if all the medusae die off.

In short, sex provides the genetic lottery ticket. The asexual polyp stage cashes in that ticket for a massive payout when the winning numbers (environmental conditions) come up. It's a brilliant two-pronged strategy.

Common Questions About Jellyfish Sexual Reproduction

Q: Can a single jellyfish reproduce on its own (hermaphroditism)?

A: Most common jellyfish species have separate sexes. However, some species are sequential hermaphrodites, starting life as one sex and changing to the other. True simultaneous hermaphrodites (producing both sperm and eggs at once) are rare in jellyfish but do exist in a few species.

Q: How long does it take from fertilization to a new adult jellyfish?

A: It varies wildly by species and environment. For a moon jellyfish in warm water, the planula might settle in days, the polyp can develop in weeks, and strobilation might occur within a few months. The ephyra then takes several weeks to months to grow into a sexually mature medusa. So, the full cycle can take less than a year, or it can be prolonged over multiple seasons if the polyp waits.

Q: Is climate change affecting how jellyfish reproduce sexually?

A: This is a major area of research. Warmer waters may extend the reproductive season, allow polyps to strobilate more often, and increase the metabolic rates of medusae. Combined with overfishing (removing their predators and competitors) and ocean acidification (which may not harm polyps as much as other species), these changes are linked to more frequent and larger jellyfish blooms in some regions. Organizations like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) monitor these trends closely.

Q: Do jellyfish mate or just release gametes?

A: The vast majority just release gametes into the water (broadcast spawning). There's no mating, courtship, or pairing up. However, as mentioned, box jellyfish and some others show more complex behaviors, with physical transfer of gametes, which is closer to what we'd call mating.

Observing and Learning More

If you're as intrigued by this as I am, you can see parts of this cycle yourself. Many public aquariums culture jellyfish and sometimes display the polyp and ephyra stages in behind-the-scenes or special exhibits. Watching a polyp strobilate under a microscope is an unforgettable sight—it's like seeing science fiction become real.

For those wanting to dive into the primary science, the research coming from marine institutes is incredible. The Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) uses deep-diving robots to study deep-sea jellyfish life cycles we know almost nothing about. The work of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution has been fundamental in understanding the physiological triggers of reproduction. These resources are gold mines for the truly curious.

So, the next time you see a jellyfish, whether in an aquarium or the sea, you'll see more than just a blob. You'll see the sexual, swimming end of a bizarre and brilliant life story, with its hidden, anchored beginning waiting somewhere out of sight. It's a testament to the incredible and often counter-intuitive ways life finds a way to perpetuate itself.

And that, from start to finish, is the full, strange, and wonderful story of how do jellyfish reproduce sexually.

Comment