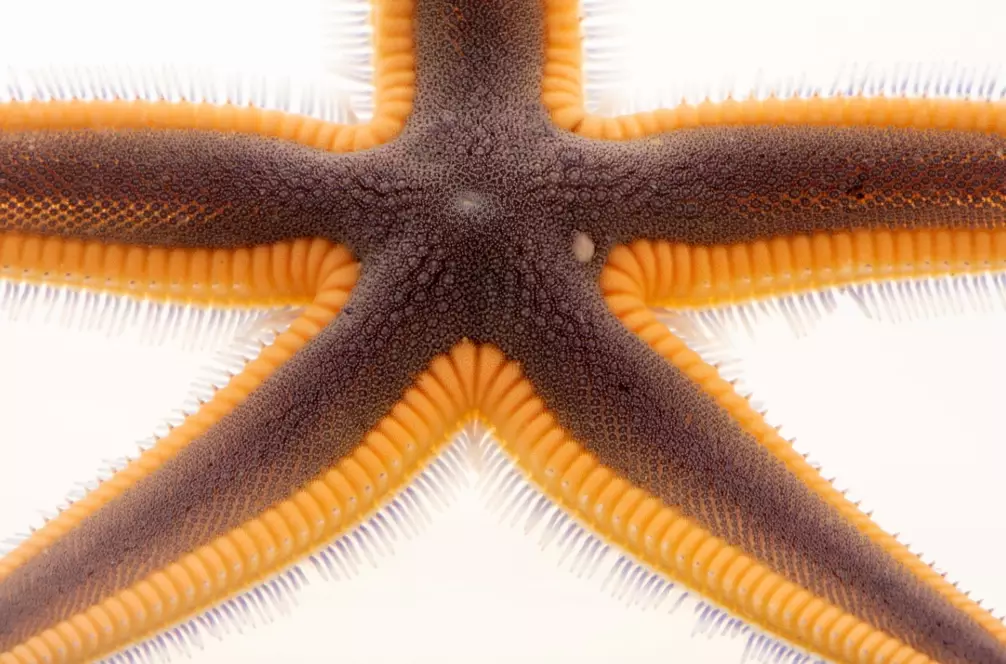

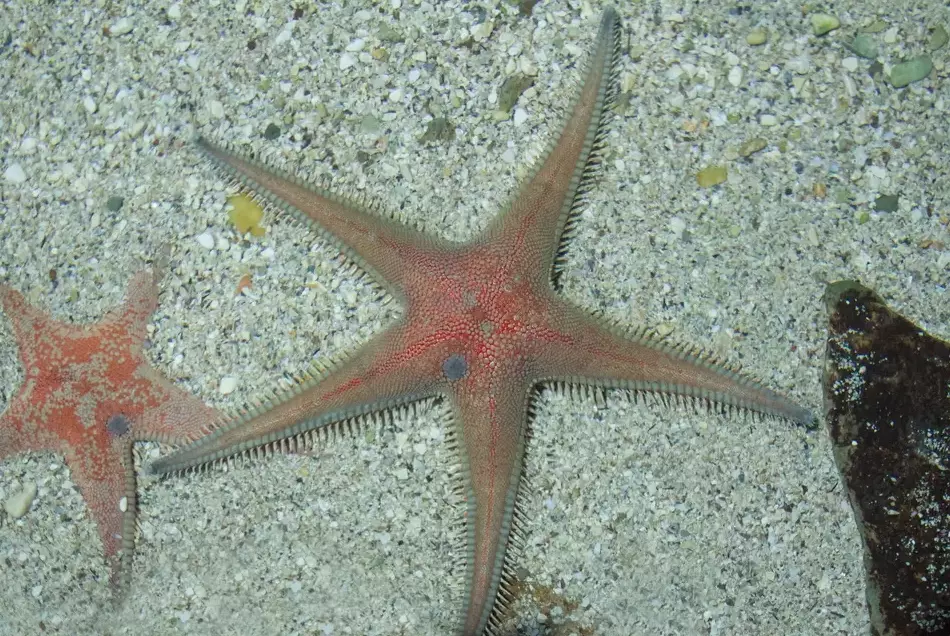

You're gliding over a sandy seabed, the sun cutting through the water in shafts of light. Then you see it—a burst of deep purple and bright orange, perfectly symmetrical, looking almost too vivid to be real. That's your first encounter with the royal starfish, *Astropecten articulatus*. It's not the most famous sea star, but for those who know where to look, it's one of the most striking residents of the Atlantic's shallow bottoms. This isn't just a list of facts. This is a guide from someone who's spent years on and in the water, learning where they hide, how they live, and the common mistakes people make when trying to find them. Let's start with the obvious. The royal starfish gets its name from its regal coloration—typically a rich, dark purple or violet central disc and arms, bordered by a brilliant orange or red margin. It usually has five arms, but I've seen the occasional six-armed individual, which always feels like finding a lucky coin. They're not giants; most span between 4 to 8 inches (10-20 cm). But here's what most websites don't tell you: the color intensity isn't fixed. A starfish living in darker, muddy sediment might appear more muted, while one in bright white sand can look shockingly vibrant. It's an adaptation, not just decoration. Their diet reveals their character. They are infaunal predators, meaning they hunt prey buried in the sand. Their favorite meal? Bivalves like small clams and snails. They don't have the tube feet with suckers that many starfish use to cling to rocks. Instead, their tube feet are pointed, perfect for digging and locomotion across soft sediment. They can bury themselves remarkably quickly if they sense danger. A quick note on terminology: Many scientists and conservationists now prefer the term "sea star" over "starfish," as they are echinoderms, not fish. However, "royal starfish" remains the widely recognized common name. I'll use both terms interchangeably here. If you're looking for them on coral reefs, you'll be disappointed. This is the first major mistake hopeful spotters make. *Astropecten articulatus* is a creature of soft bottoms. Their world is sand, silt, and seagrass. Their preferred real estate includes: Sandy Flats Adjacent to Seagrass Beds: The seagrass provides food and shelter for their prey, making the nearby sandy patches a perfect hunting ground. Look in calm bays, lagoons, and coastal inlets. Shallow Subtidal Zones: They are most commonly found from the low tide line down to about 30 meters (100 feet). I've had incredible sightings in water so shallow my fins were almost breaking the surface. Geographic Range: Your best bet is the western Atlantic Ocean. They are commonly reported from North Carolina down through the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, all the way to Brazil. I've personally had consistent luck in the Florida Keys, around Bonaire (especially on the leeward side's sandy slopes), and in certain protected bays in The Bahamas. Timing matters. They are often more active at night, but you can find them during the day, sometimes partially buried. A falling tide that exposes sandy flats can be a great time for shoreline observation. This is critical. Confusing the harmless royal starfish with the notorious crown-of-thorns starfish (*Acanthaster planci*) is a common error with significant implications. The crown-of-thorns is a major predator of live coral and has been responsible for devastating reef outbreaks. It's also covered in long, venomous spines that can cause painful wounds. Mistaking one for the other spreads misinformation and unnecessary fear. Royal Starfish (*Astropecten articulatus*): Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (*Acanthaster planci*): See the difference? Habitat is your first clue. On sand = possibly royal. On coral = definitely not royal, and possibly a crown-of-thorns. Finding one is a thrill. Your instinct might be to pick it up for a photo. Resist it. Starfish breathe and manage internal water pressure through specialized structures on their skin. Handling them, especially removing them from the water, can cause significant stress, introduce air into their system, and damage their delicate tissues. That beautiful color can fade quickly if they are distressed. Best practices for a responsible encounter: Look, don't touch. Use your eyes or a camera. Get low and observe from a respectful distance. Watch your fins and gear. In shallow sandy areas, it's easy to stir up sediment or accidentally kick a partially buried animal. Maintain good buoyancy control. Never attempt to relocate one. They are precisely where they need to be. Moving them disrupts their feeding and can expose them to predators. Report unusual sightings. If you see a large number of dead or dying starfish (of any species), it can be a sign of environmental stress. Consider reporting it to a local marine research station or conservation group, such as those affiliated with the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF). Myth 1: "They are extremely rare." Myth 2: "Their color is always purple and orange." Myth 3: "They can regenerate arms as easily as other starfish." Myth 4: "They are good pets for a saltwater aquarium." The royal starfish is a testament to the diversity of life not on the bustling coral reef, but on the quieter, expansive seafloor. Its striking appearance is a reward for those who take the time to scan the sand. Remember the key points: look on soft bottoms in the western Atlantic, appreciate its harmless nature, and always observe without disturbing. The next time you're floating over a sandy patch, slow down and look closely—you might just spot the monarch of the mud. Where is the best place to find a royal starfish while snorkeling? Forget the deep reef drop-offs. Royal starfish, or *Astropecten articulatus*, prefer sandy or muddy bottoms adjacent to seagrass beds, often in surprisingly shallow water from just 1 to 30 meters deep. I've had my best luck in calm bays and lagoons on the Atlantic coast, particularly around Florida and the Caribbean. Look for their distinctive track marks on the sand at low tide. They're not climbers; you won't find them clinging to coral walls. Is the royal starfish dangerous to humans like the crown-of-thorns? No, and this is a crucial distinction. The royal starfish is completely harmless to humans. It lacks the long, venomous spines of the crown-of-thorns starfish. Its arms have a rough, granular texture but pose no threat. The real danger is to them from us—always observe without touching, as the protective mucus layer on their skin is vital for their health. Focus on three key features most guides miss. First, check the arm tips: royal starfish have pointed, almost sharp-looking tips, not blunt or rounded. Second, look at the color pattern: it's not just purple and orange; the vivid orange is typically confined to the margins of the arms and the central disc, creating a stark border. Third, observe the underside (oral side). If you gently flip one over (in your mind, don't actually do it!), you'll see prominent, yellowish ambulacral grooves running down each arm, which they use for movement and feeding. What do royal starfish eat, and should I feed them? They are carnivorous scavengers and predators, primarily feeding on bivalves like clams and snails buried in the sediment. They use their arms to dig and then extrude their stomach to digest the prey externally. You should never, under any circumstances, attempt to feed a wild starfish. Introducing foreign food disrupts their natural foraging behavior, can harm their digestive system, and pollutes the water. The best practice is silent observation.

What's Inside This Guide

Royal Starfish 101: Beyond the Pretty Colors

Where to Find Royal Starfish: Prime Habitats and Locations

Don't Mistake It: The Royal vs. The Destructive Crown-of-Thorns

Side-by-Side Comparison

- Arms: 5 (rarely 6), slender, pointed tips.

- Surface: Granular, rough texture with small, blunt spines or plates.

- Color: Solid purple/violet with distinct orange margins.

- Habitat: Sandy/muddy bottoms.

- Diet: Buried bivalves (clams, snails).

- Danger to Humans: None.

- Danger to Reefs: None.

- Arms: Many (often 10-20), thicker, rounded tips.

- Surface: Covered in long, sharp, venomous spines.

- Color: Variable—blue, purple, red, brown, often mottled.

- Habitat: Coral reefs.

- Diet: Live coral polyps.

- Danger to Humans: Painful, venomous stings.

- Danger to Reefs: Extreme—major coral predator.

How to Observe and Protect Royal Starfish

Clearing Up Common Myths About the Royal Starfish

Not true within their range and habitat. They are often overlooked because people aren't looking in the right place—on the sand, not the reef.

While this is the classic pattern, color can vary. I've seen specimens with more maroon or burgundy tones.

All sea stars have some regenerative ability, but it's a stressful and energy-intensive process. A royal starfish with a damaged arm is more vulnerable to predation and disease.

They are not. Their specialized diet of live buried bivalves is nearly impossible to replicate in a home aquarium. They almost always starve slowly, which is cruel.

Conclusion

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I be sure I'm looking at a royal starfish and not another species?

How can I be sure I'm looking at a royal starfish and not another species?

Royal Starfish Guide: Habitat, Facts & How to See Them

Comment